Research shows that in a number of settings – such as hospitals and universities – there is a correlation between the 'expert knowledge' of the leader and organisational performance.

In their 2015 paper, A Theory Exploring How Expert Leaders Influence Performance in Knowledge-Intensive Organizations, Amanda Goodall and Agnes Bäker digest research on how expert leaders affect organisational performance. They argue that: "Experts and professionals need to be led by other experts and professionals, those who have a deep understanding of and high ability in the core-business of their organization."

Goodall followed this in 2016 when she looked at expert leadership in psychiatry. Goodall found that the presence of a physician as

In universities, research also suggests that the most respected scholars lead the best universities with the quality of the research quality of those universities improving in subsequent years.

This got me thinking about whether CEOs of multi-academy trusts (MATs) need to have been headteachers, or whether they can just be good general leaders. I use both the 2015 and 2016 research above to discuss the link between leadership and

A theory of expert leadership

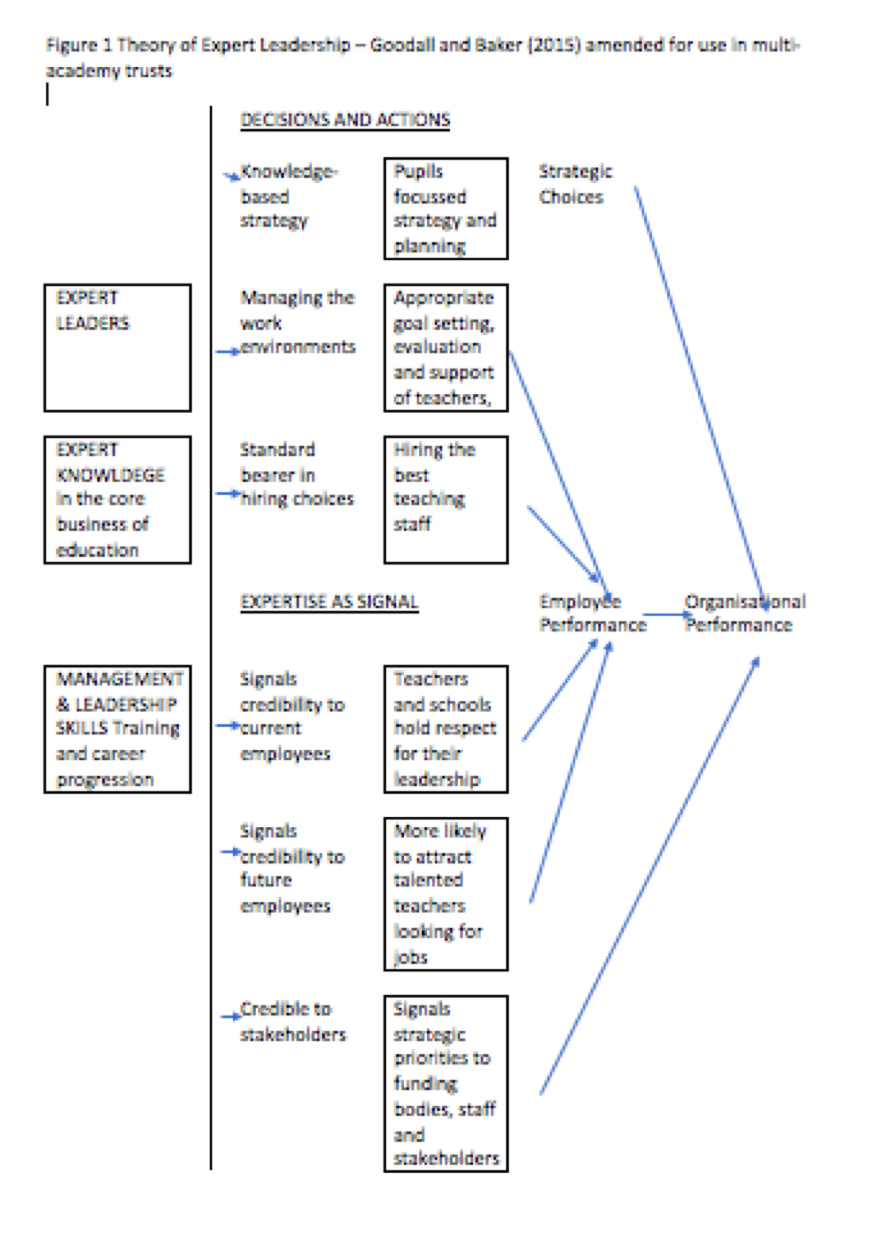

The image below illustrates Good and Baker's theory of expert leadership. In particular, it shows how expert leaders transfer their influence and how they – compared with 'generalists' – signal their expertise and influence organisational performance.

Goodall notes that there are three aspects of the model which could explain the performance difference between 'expert leaders' and professional managers:

1. Knowledge-based strategy. The priorities of the expert leader/headteacher are in all likelihood different from the professional manager, for example, in an MAT, an experienced headteacher might be more likely to put pupil needs first.In addition, expert leaders are likely to have engaged deeply with colleagues, pupils and parents, which will inform operational and strategic choices.

2. Manage the work environment for employees. Expert leaders/headteachers have come up with 'through the ranks' and understand teachers' professional culture and values more deeply than non-experts and professional managers.They will also have a greater understanding of performance indicators – both formal and informal – which could affect performance.

3. Hiring behaviour. It is easier to hire 'talent' if the expert leader has already met the standard set by the organisations. All other things being equal, expert leaders may be more likely to recruit other outstanding individuals.

Goodall also notes that expertise signals certain things that can also affect organisational performance. It does so in three ways:

1. Signals credibility to employees. Expert leaders are more likely to command respect because of their track record of success as a headteacher and teacher.

2. Signals credibility and strategic priorities to potential employees. This is because the reputation of the expert leader may be some of the information that a potential employee may be able to pick up about an organisation.

3. Credible to stakeholders. The board of a MAT may wish to appoint an expert as way of signalling to stakeholders and others.

So should we have expert leaders in MATS?

The first thing to note about the research is that measuring the impact of expert leaders on organisational performance is really complex. In 2009, researcher Tim Simkins and

●Outcomes are complex, difficult to specify in simple terms and may include unintended or unexpected consequences (both positive and negative) as well as intended ones

●The most important effects are indirect, occurring through the leaders' influence on others who, in turn, can influence desired final school outcomes;

●These effects do not occur instantaneously – it takes time for learning to become embedded in changed behaviour, for leaders' influence processes to have effects on others, and for these changes to impact on teaching and learning and hence on pupil outcomes…(p36)

What's more, if one of the main ways experts affect performance is through their strategic choices, then this calls for professional judgment.However, as Daniel Duke notes in his recent paper on the preparation and judgement of education leaders, very little attention has been paid to how – and if – educational leaders can be trained to develop the quality of their professional judgment.

It is also important to be aware of the difference between the rhetoric and the reality of being credible to

Nor is it enough just to be an expert leader – you also need to basic managerial competence.What's more, it's worth remembering that – as Leithwood et all shows in their 2008 paper – school leadership only accounts for a very small percentage of the difference in performance between schools (once pupil background is taken into account).

So while it might be appealing to believe that MATs should be led by expert leaders – those who have a deep professional background in education, such as headteachers – it's only when long-term research has taken place that we will have any kind of substantive evidence-base with which to inform the appointment of CEOs. Until then, it's probably best not to cherry-pick the evidence in accordance with our professional preferences.

This is an edited version of an article that originally on Gary Jones's blog here.