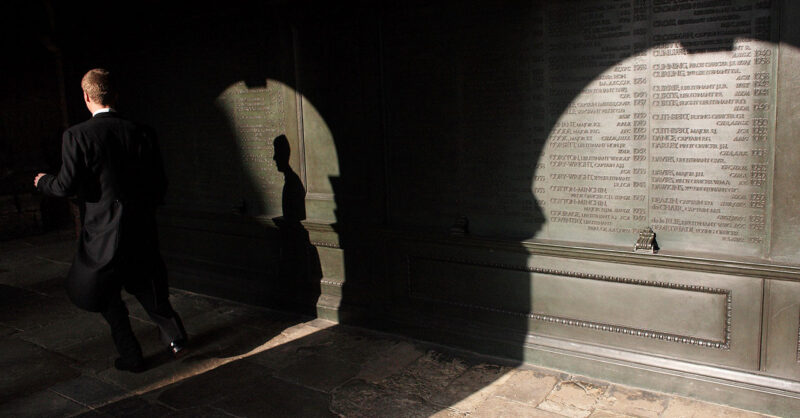

Costing almost £50,000 a year, an Eton education is the pinnacle of privilege. Not only will an Eton-educated child probably achieve the highest grades and a place at one of the world’s most prestigious universities, but they’ll have spent their formative years doing algebra with future politicians and playing polo with heirs to thrones around the globe. Given that 20 British prime ministers were educated in Eton’s hallowed halls, attending puts you on a pretty firm trajectory to the loftiest seats of power.

It was announced on 22 August that Eton will open three selective sixth forms in the north of England and the West Midlands, in partnership with the high-performing chain of state schools Star Academies. On the surface, exporting an Eton education to deprived northern regions (Dudley, Middlesbrough and Oldham) seems positive for social mobility and easing the north-south divide.

But if my seven years as a state school teacher have taught me anything, it is to be sceptical of headline-grabbing schemes that promise to solve with a single innovation the deeply rooted problems in education. The Eton scheme may sound revolutionary, but it misses the point entirely.

It’s worth asking whether elite schools such as Eton truly are academically superior. Has it cracked the code for excellent teaching, or does it simply benefit from having students who aren’t so worried about being evicted that they can’t turn in their physics homework.